J.C. Harden helped bring current to the country

Published 8:56 pm Friday, October 22, 2021

- File Photo The Johnson Center for the Arts will host an artist’s reception for Mary Ann Casey from 6 until 7:30 Wednesday. The public is invited. Pictured is some of Casey’s artwork included in the exhibit.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

People who lived in rural Pike County were kept in the dark until 1937.

J.C. Harden of the Shiloh Community dreamed of having current and basking in the convenience that would come with it.

For so long it was only a dream, but one bright, June day in 1937, Harden heard that a meeting was going to take place at the courthouse on the center square in Troy.

They were going to talk about getting current out to folks that lived in the country said Harden who was a mule farmer. He knew what electricity would mean to the farming community, so he laid down his plow and went to town.

“There was a pretty good crowd there because we all wanted current,” Harden said.

“They talked about a lot of things we didn’t know the first thing about. I had to ask a lot of questions, trying to learn.”

Harden asked more questions than all the others put together. When the meeting was over his name was called as the one to canvas his community to see if there was enough interest to make a line profitable.

“I’d hauled feed to country stores for my daddy so I knew a good bit about the community,” Hard-en said. “And, I’d passed Mose Hollis’ dairy a lot of times, so I knew they had current. I had no better judgement than to think they would tie on to his house and run the line down Highway 29.”

Banking on his judgement and the realization that sharecroppers and tenant farmers couldn’t afford electricity, Harden concentrated on homeowners who lived in painted houses and were better advanced than others.

“We had to have four to five customers per mile to get current run and the membership was five dollars. Back then that wasn’t a lot, but it wasn’t a little either.

“One day a lady bucked at the $5 membership. She said she could buy herself a dress for that amount. I told her, ‘lady if you’ll sign on, I’ll buy you a dress.’ Current would improve the quality of rural life with a flip of the switch.”

Harden and his wife, Gladys, had experienced a few modern conveniences and they were to their liking.

After taking over the womanly chores after his wife had a baby, Harden was ready to pull out the pocket book when a washing machine salesman came calling.

“Back in those days a woman had to stay in bed nine days after she had a baby,” Harden said. “That was a lot of time for a man to be over a washtub.”

So, Harden happily unloaded a gasoline, kick-start wringer washing machine onto the back porch.

“You still had to draw the water, boil it in the pot and pour it into the washing machine, but the ma-chine did the scrubbing,” he said.

“There was no switch to flip-start the machine; it was a kick-start operation but, once you got it started, it saved a lot of backbreaking work.”

Also, Harden had purchased a battery-operated radio early that year. He and his family knew a little about conveniences, but they could only imagine what electricity would mean to their way of life.

Harden said they were too poor to own an icebox, but he would splurge about once a month and buy a block of ice. Otherwise, they depended on the well to cool their milk.

Without any way to keep food cool that was left from the day’s meal, it went straight into the slop bucket to be fed to the hogs the next afternoon.

“That’s where hogs got their salt– from the slop bucket,” Harden said.

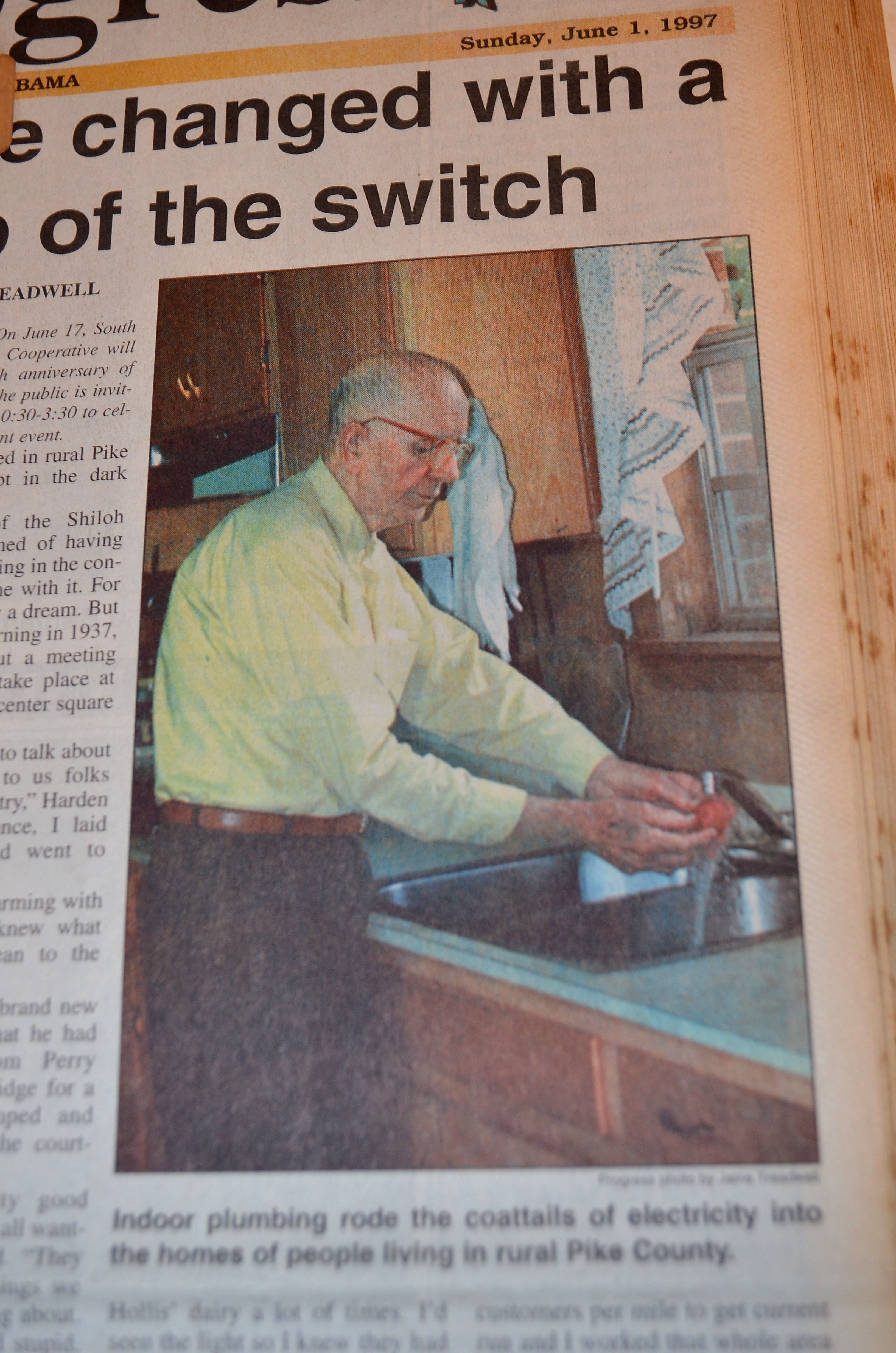

Pumps and outhouses were commonplace among country folks.

“And, at night, we brought out the slop jars and the chambers,” Harden said. “We didn’t know what an inconvenience that was because everybody was in the same condition.

If you went to visit, your neighbor had an outhouse. If your neighbors came to visit you, you had an outhouse. That was hard times, but we didn’t know it.”

About a year after Harden canvassed the county for membership into the rural electric company, the switch was flipped and life changed for the better.

The lines had been run; houses had been wired and the customers were anxiously waiting for the lines to come on.

“One day, around dinner time, all of a sudden, a light came on. I just hollered and hollered. The children ran around the house from room to room turning on the lights,” Harden said.

One neighbor rang up another, “You got current?! You got current?!

“I’ve got it! Oh, I’ve got it!” was the reply.

“That was the happiest day of my life for small things,” Harden said. “You just don’t know what lights and refrigeration meant to us.”

Just as quickly. As the switch was flipped, life became better.

“We stayed up later at night because we could read,” Harden said. “We had cold milk and it was, oh, so good. For the first time the slop bucket was empty because we had leftovers in the refrigerator. I guess the hogs were the only ones that didn’t benefit when current came to the country.”