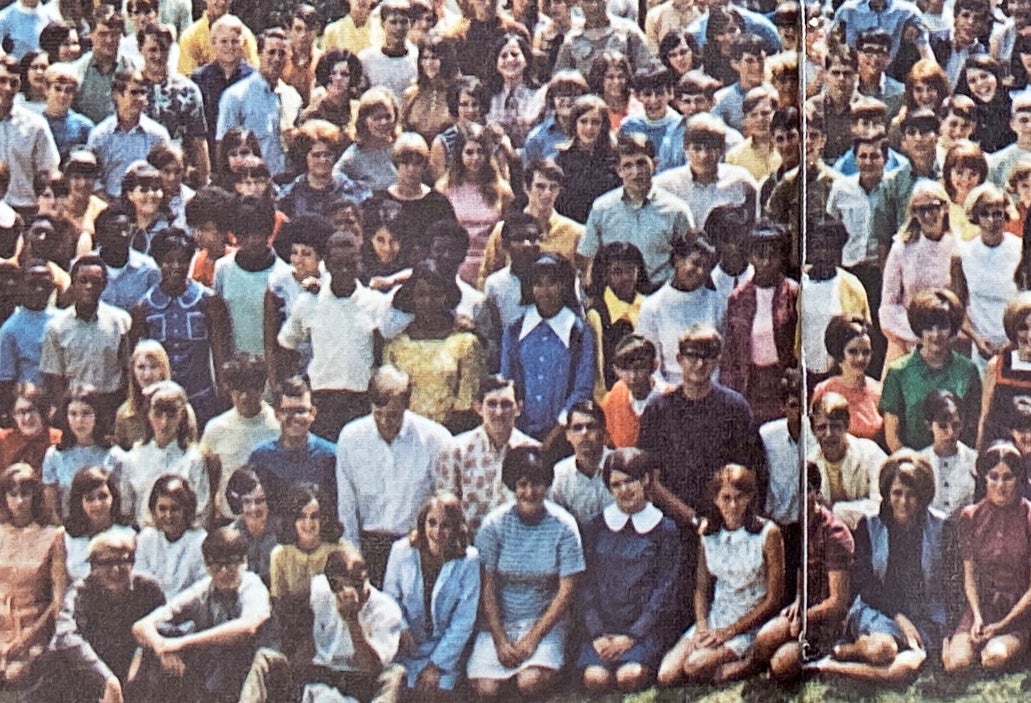

INTEGRATED: Students remember smooth desegregation process

Published 9:20 pm Wednesday, February 19, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The integration of public schools was a tumultuous time across the country, but the first students of an integrated Charles Henderson High School remember a comparatively smooth transition.

“In comparison to the rest of the country, it was a cakewalk, you know?” said Willie Jones, who was among the first African-American students to come over to CHHS. “At that time there was tensions on both sides of the room. But the people there found a way to cope. Not only did the kids find a way, the instructors found a way to breathe it in very slowly and learn as we go. It was a great experience.”

According to Reunion Troy historian Nicklaus Chrysson, the city began its desegregation plan in 1965, 11 years after the Supreme Court issued a ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that ordered the end of segregated education.

Dr. Eddie B. Warren was also among the first group of African-American students to leave Academy Street High School to join the previously all-white CHHS.

“I went there for my sophomore through senior year,” Warren said. “At that point in time, it was a choice; students that wanted to transfer over could and others were not required to. There was a small number of students who got together and decided to transfer. There was a little bit of apprehension at the time as we could see what’s going on in other parts of the country. But that degree of apprehension very quickly went away. I didn’t encounter anything that was overtly negative or hostile. It was surprising how pleasant it was. We just did not have the situations that other schools had.”

Steve Flowers, a white member of that initial integrated class, said the process was smooth despite the circumstances.

“Young white southerners had grown up thinking segregation was the way, but it went smoothly in Troy, much smoother than in other places,” Flowers said.

Athletics played a key role in bringing the students together as they operated as a team.

“Head Football Coach Frank Sadler taught us that we bleed together, sweat together, cry together and laugh together,” Jone said. “By the time September came around, he had instilled a winning spirit in us. You can’t win as one; you have to win as a team. We came together on that point and have been together ever since.”

Jones recounted one night when the two black players on the football team were denied service on an away trip.

“We had the band and the team and everything, more than 100 people – it would have been a big business night,” Jones said.” But our coaches said if you’re going to feed one, you’re going to feed everybody. So we got back on the bus and when we got back to Troy – Ingram’s restaurant was in business at that time – somebody had called them and they had food ready for us.”

Flowers recounted another time when the basketball team traveled to play Luverne, a team that had not yet integrated.

“We had a lot of rough old white men who came on the court and started fighting,” Flowers said. “We would get a lot of catcalls too. It wasn’t so bad in football where you couldn’t tell what the crowd was saying.”

But despite the pushback from other schools, Jones said the school always supported its students.

“The student body and faculty from CHHS was always there and backed us up,” Jones said. “It never got blown into something else because it was the entire student body.”

The leadership of Principal Henry Greer was remembered fondly by all of the classmates.

“Mr. Greer was the principal of all principals,” Warren said. “He really held the school together.”

“He was one of the finest men I’ve met,” Jones said. “Things could have easily gotten complicated, but he showed it didn’t have to be as complicated as people try to make it.”

By 1970, the school had fully integrated and Academy Street High School closed its doors in 1971.