There’s the rub

Published 9:35 am Monday, January 16, 2012

Anyone who knows Ann Kelly Williams can easily envision her crawling around a crypt in pursuit of something that will enlighten her life.

But even her 80-year-old mom was a bit taken aback to Williams engaged in such an activity many years ago.

“My mother said, Ann, what in the world are you doing up there?” Williams said, laughing.

What she was doing “up there” was making a brass rubbing of Anne Boleyn’s father’s tomb at St. Peter’s parish church in the village of Hever in England.

Making brass rubbings was not new to Williams. “Brass Rubbing had become an interest of hers. A hobby of sorts. A passion, perhaps.

“The way I got started making brass rubbings was through a friend,” Williams said. “She was building a new house and she wanted a brass rubbing for the library. She began to ask around and found that brass rubbings cost a lot of money.”

Williams’ late husband, Red Williams, worked for The Boeing Company and traveled widely.

“Red was in Europe a lot and I got to go with him,” Williams said. “My friend’s interest in brass rubbings had spurred my interest in them. It was there in England that I got to do my first brass rubbing and I was fascinated with the process.”

A brass rubbing is an accurate replication of a brass portrait of a medieval person that was placed on ancient burial vaults.

The original brass monumental life-sized portraits were made by 12th to 17th century European artists. They depicted knights in full armor, kings, queens, lords and ladies in court or religious dress and other costumes that represented wealthy medieval occupations. “Brass rubbings are all about history,” Williams said. “When you do brass rubbings, you learn about the people and how they died. It just piques your interest in the people and places of hundreds of years ago.”

Williams said one brass rubbing that she did was of an English general who fought wars in Russia and Prussia while his wife was home with 12 children. “It took a long time to get to Russia, so I wondered how he managed to have 12 children, Williams said, laughing. “While doing brass rubbings, you learn a lot of history and have fun at the same time.”

Over the years, Williams’ collection of brass rubbings grew to 30 and more. Most of them were done at Westminster Abbey.

Williams didn’t know when she was crawling around “up there” on crypts that brass rubbings of the ancient tombs would soon become a thing of the past.

“Brass rubbings became popular after World War II so much so that, in time, the rubbings were wearing down the images,” she said. “So, since the late 1970s, brass rubbings are no longer allowed in England. Molds have been made of many of the images and you can make rubbings from the molds but not of the ancient tombs. I am very proud of the rubbings that I made before the law was passed.”

Williams has donated 10 rubbings from her collection to the Johnson Center for the Arts in Troy and is planning to donate several others. “You just can’t keep these large, framed rubbings around the house,” she said, laughing. “And, too, I want others to have the chance to see these original brass rubbings. They are history and they are art.”

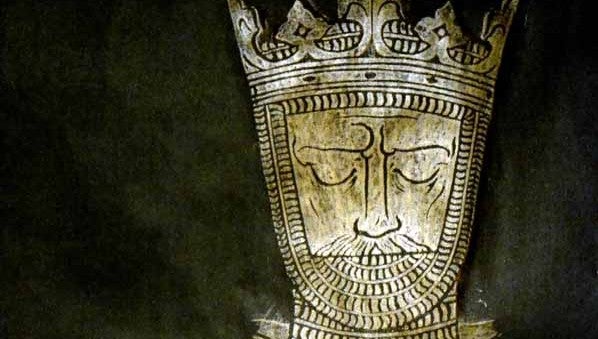

When Williams was a tour guide at the museum at the University of Tennessee during the late 1970s, she made a mold of the bust of Robert the Great, who was Richard Lionhearted’s highest man.

“I wanted to have the mold so that the children could make brass rubbings and learn about the art form,” she said. “Rubbings are not made with chalk. They are made with a wax crayon, called heelball. You have to rub very hard and firm with the wax crayon so it takes a good bit of energy to make a rubbing. The paper that you use is like butcher’s paper. You can rub really hard on it and it won’t tear.”

Williams said most rubbings are done with a black crayon but rubbing crayons also come in silver, gold and bronze.

“You can order brass rubbings from different churches and castles in England and they cost about $200,” she said. “Original rubbings made from the ancient tombs are very expensive.”

Williams said Europeans are very protective of their works of art, especially the ancient art.

“When brass rubbings of the ancient tombs was permitted, the churches made a lot of money,” she said. “You had to pay to do the rubbings and it was about $50 an hour. But, when it was realized that the rubbings were wearing down the images, it was stopped.”

Williams said that, during times of war, a church in Fairford, England took out its stained glass windows and buried them so they wouldn’t be destroyed. The British realize the value of their art and, because they do, it has been preserved and continues to be protected by law.

Those who had the opportunity to “crawl around crypts” and make brass rubbings of the ancient tombs know how fortunate they are. That opportunity will not be again. However, because molds were made of the ancient tombs, others will be able to experience the process. Williams has made the mold of Robert the Great available to the Johnson Center for the Arts. Those who visit the art center during the months of January and February will have an opportunity to make a brass rubbing of their own.